ПАРАЗИТОЛОГИЯ, 2019, том 53, № 6, с. 443-455.

УДК 576.895.121

ON CYSTICERCOIDS OF THE GENUS FLAMINGOLEPIS

SPASSKIJ & SPASSKAJA, 1954 (CESTODA: HYMENOLEPIDIDAE)

PARASITIZING ARTEMIA FRANCISCANA KELLOG, 1906

(ARTHROPODA: ARTEMIIDAE) IN DUBAI, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

© 2019 R. K. Schuster *

Central Veterinary Research Laboratory, PO Box 597, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

* e-mail: r.schuster@cvrl.ae

Received 17.07.2019

Corrected 3.09.2019

Accepted 9.09.2019

An examination of 300 Artemia franciscana Kellog, 1906 revealed an unusual high cysticercoid

prevalence of 99 %. Large and small cysticercoids of the genus Flamingolepis were the most frequent

cestode larvae. Digestion of crustaceans in artificial gastric juice resulted in a large number of

cysticercoids of which 120 large and 60 small cysts were studied in light microscopy. A portion of the

material was used for histological examination. As a result, elliptical shaped large cysts of 345-570 x

204-387 µm with rostellar hooks of 161-188 and a blade of 91-115 µm were considered F. dolgushini

and cysts of 157-209 x 112-164 µm and rostellar hooks of 49-59 µm and a blade of 25-33 µm were

attributed to F. flamingo. The material contained another species with rostellar hooks measuring 82-84

µm that most probably belong to F. megalorchis.

Keywords: Artemia franciscana, Cestoda, Flamingolepis, cysticercoids, Dubai.

DOI: 10.1134/S0031184719060012

Brine shrimps are phylogenetically old crustaceans belonging to the order Anostraca, class

Branchiopoda. They inhabit hypersaline inland waters and can be found on all continents

except Antarctica. The genus Artemia consists of seven species with A. salina (Linnaeus,

1758) and A. franciscana Kellogg, 1906 being the best investigated ones and parthenogenetic

populations called A. parthenogenetica (Asem et al., 2010). Brine shrimps play an important

role in aquaculture as their juvenile stages is food source for fish and crayfish larvae. Artemia

spp. are also known to act as intermediate hosts for cestodes. The first description of a

cysticercoid in A. salina was done roughly 100 years ago (Heldt, 1926). A.P. Maksimova

rendered great service to the investigation of the role of A. salina as intermediate host for

avian cestodes. Working at the Tengiz lake of Kazakhstan, the author described larval stages

of 10 cestode species (Maksimova, 1973, 1977, 1981, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1991; Gvozdev,

Maksimova, 1979). Research on the role of brine shrimps as intermediate hosts for avian

cestodes in the French Camargue started in the early 1980’s (Gabrion, Mac Donald, 1980;

443

Gabrion et al., 1982) and was extended to salterns of Spain by Amat et al. (1991). Mura

(1995) examined brine shrimps in Sardinia. Georgiev et al. (2005) gave a comprehensive

description of 8 cysticercoids found in A. parthenogenetica in the Odiel Marshes in Spain.

One cysticercoid that struck due to its large dimensions and eight large skrjabinoid hooks

measuring around 180 µm was frequently found hypersaline aquatic habitats in Italy, France,

Spain, Portugal and Tunesia was attributed to Flamingolepis liguloides (Gervais, 1847) 1.

However, rostellar hooks of the adult F. liguloides were distinctly smaller and measured only

130 µm. Another frequently detected but considerable smaller cysticercoid was allocated to

Flamingolepis flamingo Skrjabin, 1914). The aim of this paper was to describe the morphology

of Flamingolepis cysticercoids in A. franciscana from Godolphin lakes in Dubai.

Material and methods

In connection with a study of Eurycestus spp. in A. franciscana collected in the Godolphin lakes

in Dubai (Schuster, 2019) there was also the possibility to examine the morphology of cysticercoids

belonging to the genus Flamingolepis that occurred in high prevalences and intensites. The Godolphin

lakes are artificial hypersaline ponds situated in the city of Dubai. A detailed description of this habitat

was given by Sivakumar et al. (2018).

The sample collected by closed meshed net consisted of several thousand A. franciscana of all

development stages (cysts, nauplii, metanauplii and adults). Part of the material was killed in hot

(70 oC) 70% alcohol. A total of 300 adult specimens were randomly selected and put for five days into

a drop of glycerin to clear the body of the crustaceans and make all cysticercoids visible. Screening

for the presence of cysticercoids was carried out at low magnification (40-100x).

Another portion of brine shrimps of the same sample was exposed for 30 min to artificial gastric

juice on a magnet stirrer at 40 oC. This portion was then washed 3 times in phosphate buffer solution

(PBS) and the sediment with hundreds of cysticerci was kept for another 3 hours in an incubator at

40 oC before it was fixed in hot 10% neutral formalin. For the morphological study, cysticercoids were

put for 24 h into 30% lactic acid to dissolve calcareous bodies that otherwise reduce the transparency

and visibility of structures of the cysticercoid. A total of 120 large and 60 small cysticercoids were

measured and the following measurements were taken: length and width of the cysticercoid, the scolex,

the suckers, the rostellum, width of cyst wall, length of the rostellar hooks and their blades. The

cercomer of the cysticercoids was not considered since it was dissolved during artificial digestion.

The majority of the material was used to prepare histological sections. For this, cysticercoids were

dehydrated in rising concentrations of alcohol and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections were

hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and periodic-acid-Schiff (PAS) stained. Examination of both cysticercoids

cleared in lactic acid and histological sections was performed an OLYMPUS BX51 microscope

connected to an OLYMPUS DP27 camera with the software OLYMPUS cellSens Dimension.

Statistical analysis

For calculating prevalence and intensity of infection at their 95% lower and upper confidence intervals

the software package Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 (QP WEB) (Rozsa et al., 2000) was used.

1 In a remark on F. liguloides, Georgiev et al. (2005) stated mildly that their material corresponds to that of Robert

and Gabrion (1991) but also that of Maksimova (1973) but believed Amat et al. (1991) that F. dolgushini is a junior

synonym of F. liguloides. In all following publications the large Flamingolepis cysticercoids were diagnosed as F.

liguloides.

444

Results

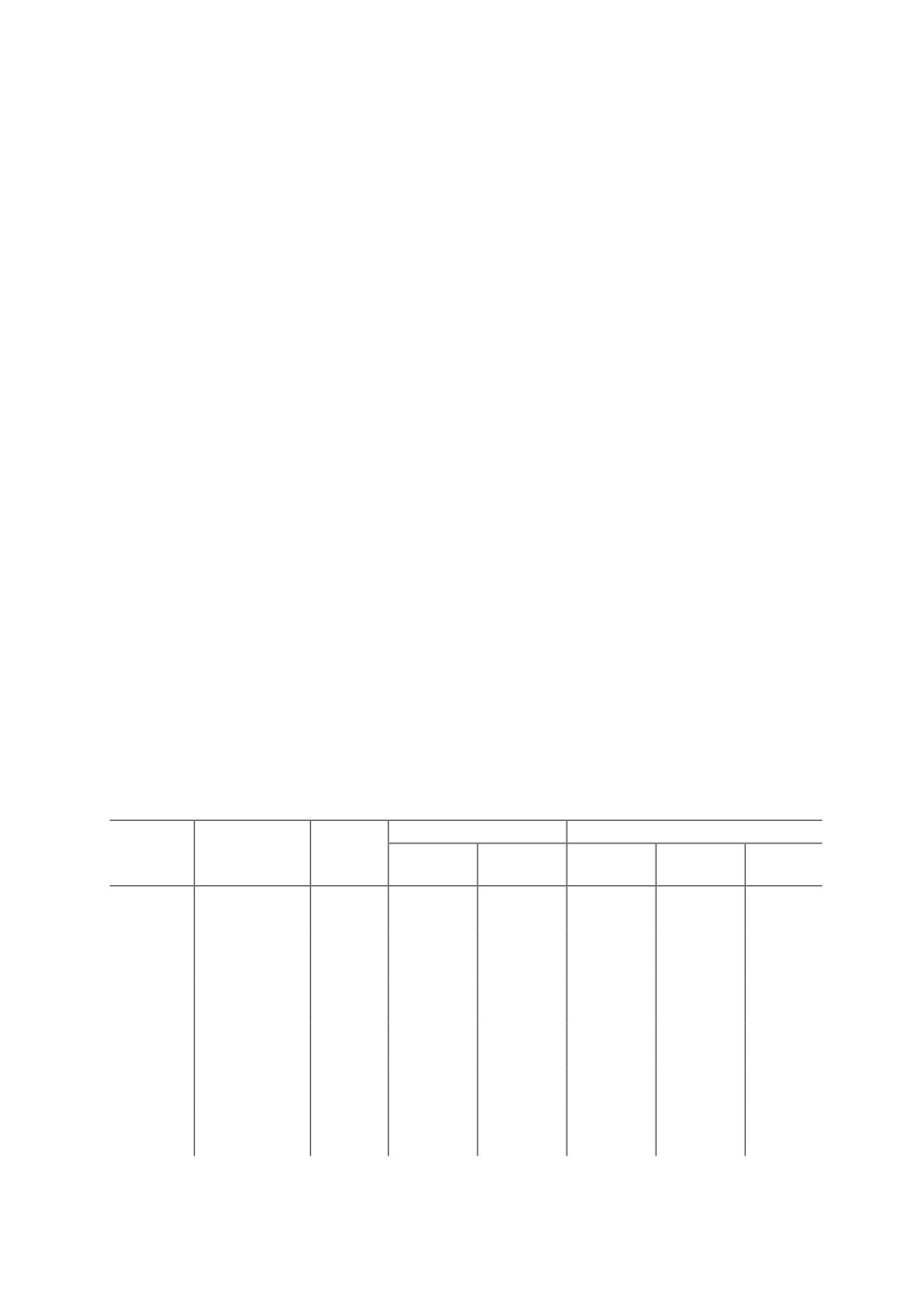

Of 300 examined A. franciscana, 134 were male of which 132 (= 98.5 %) harbored large

Flamingolepis cysticercoids (Fig. 1) in numbers between one and twelve. Of the 166 female

shrimps, 165 (= 99.4 % were infected with one to twenty-four of these large cestode larval

stages (Tab. 1). Strikingly smaller Flamingolepis cysticercoids with a long coiled cercomer

(Fig. 2) were present in 52 male (=38.8 %) and 72 (=43.4 %) female hosts. Cysticercoids

of the genus Eurycestus were diagnosed in 83 male and 104 female shrimps. A single

cysticercoid of Gynandrotaenia stammeri Fuhrmann, 1936 was detected in a female shrimp.

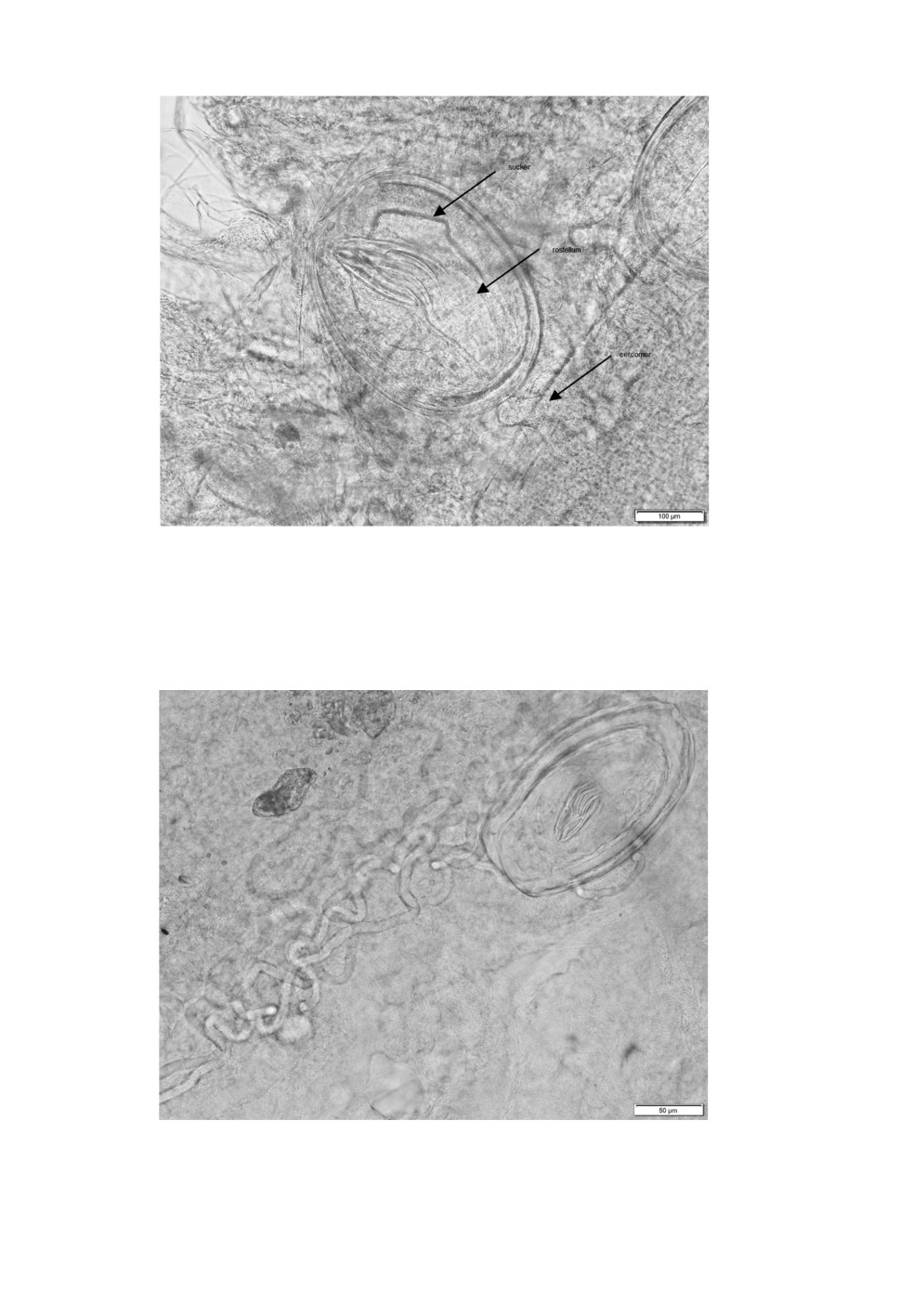

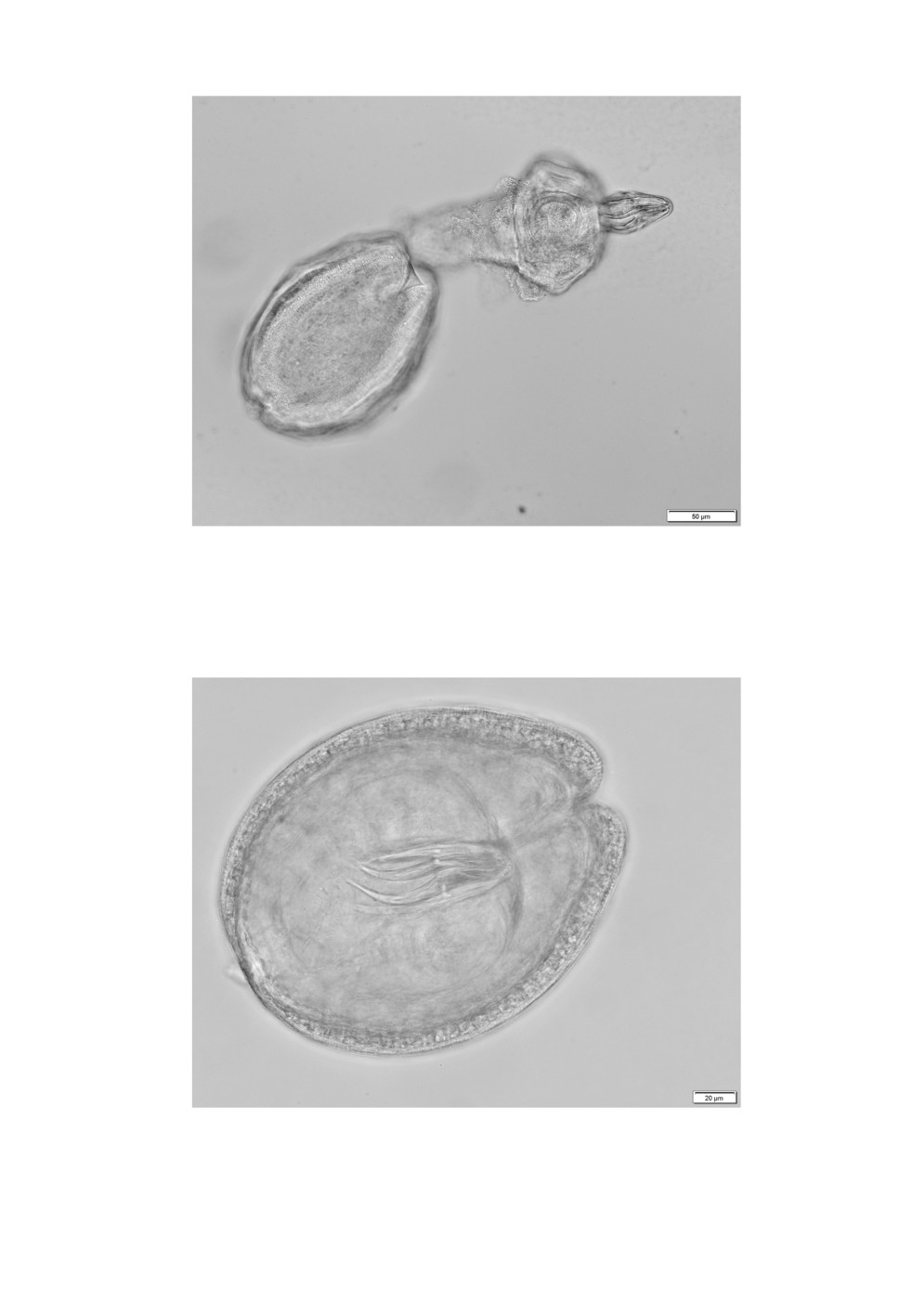

Peptic artificial digestion of fresh brine shrimps resulted in a large number of oval

shaped large (345-570 x 204-387 µm) and small (157-209 x 112-164 µm) Flamingolepis

cysticercoids (Figs 3, 4) with actively moving scolex structures. The average cyst walls of

large and small cysticercoids measured 15 µm (range 9-34 µm and 14 µm (range: 10-21 µm),

respectively. Measurements of cysts and subsequent scolex structures are given in

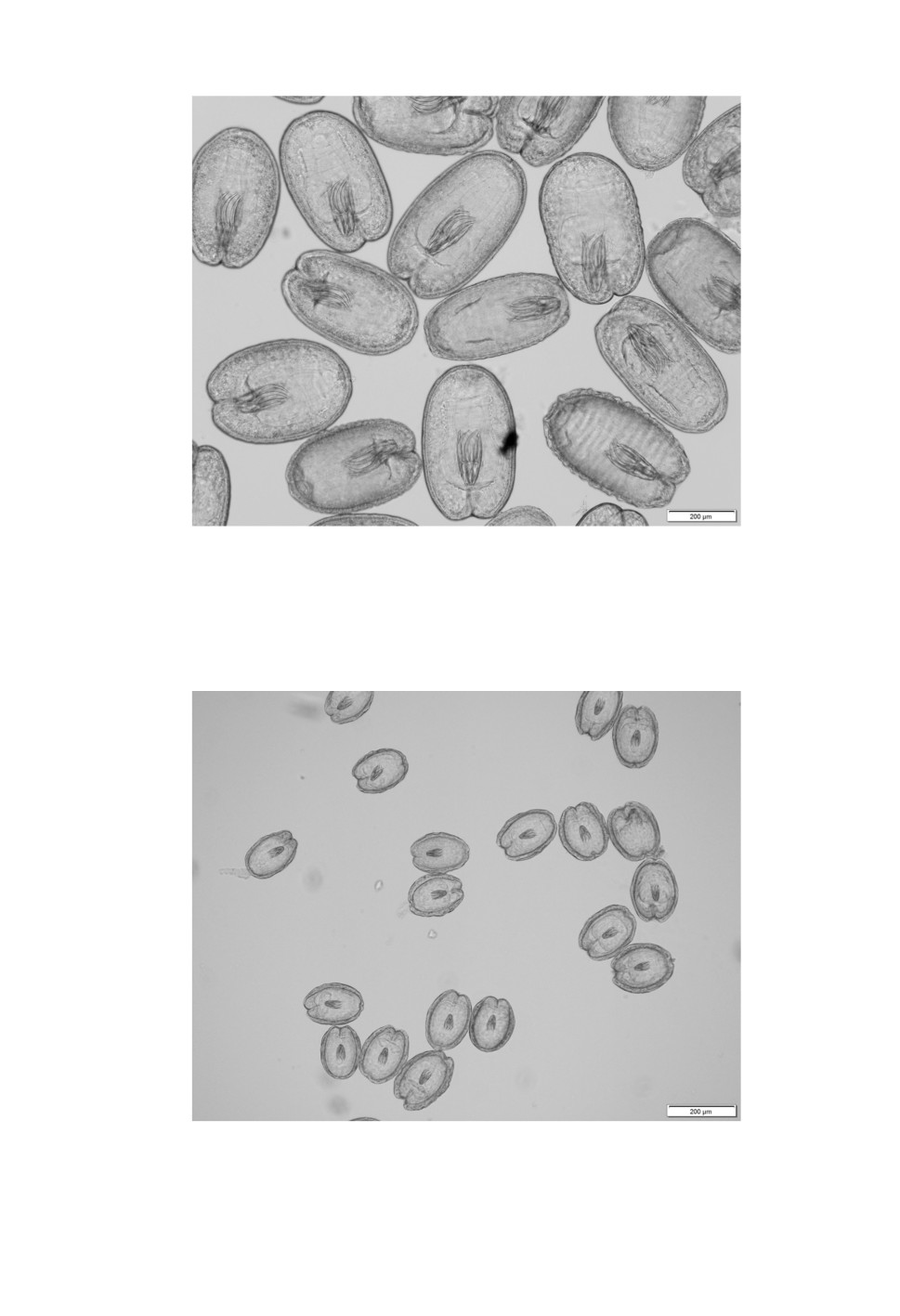

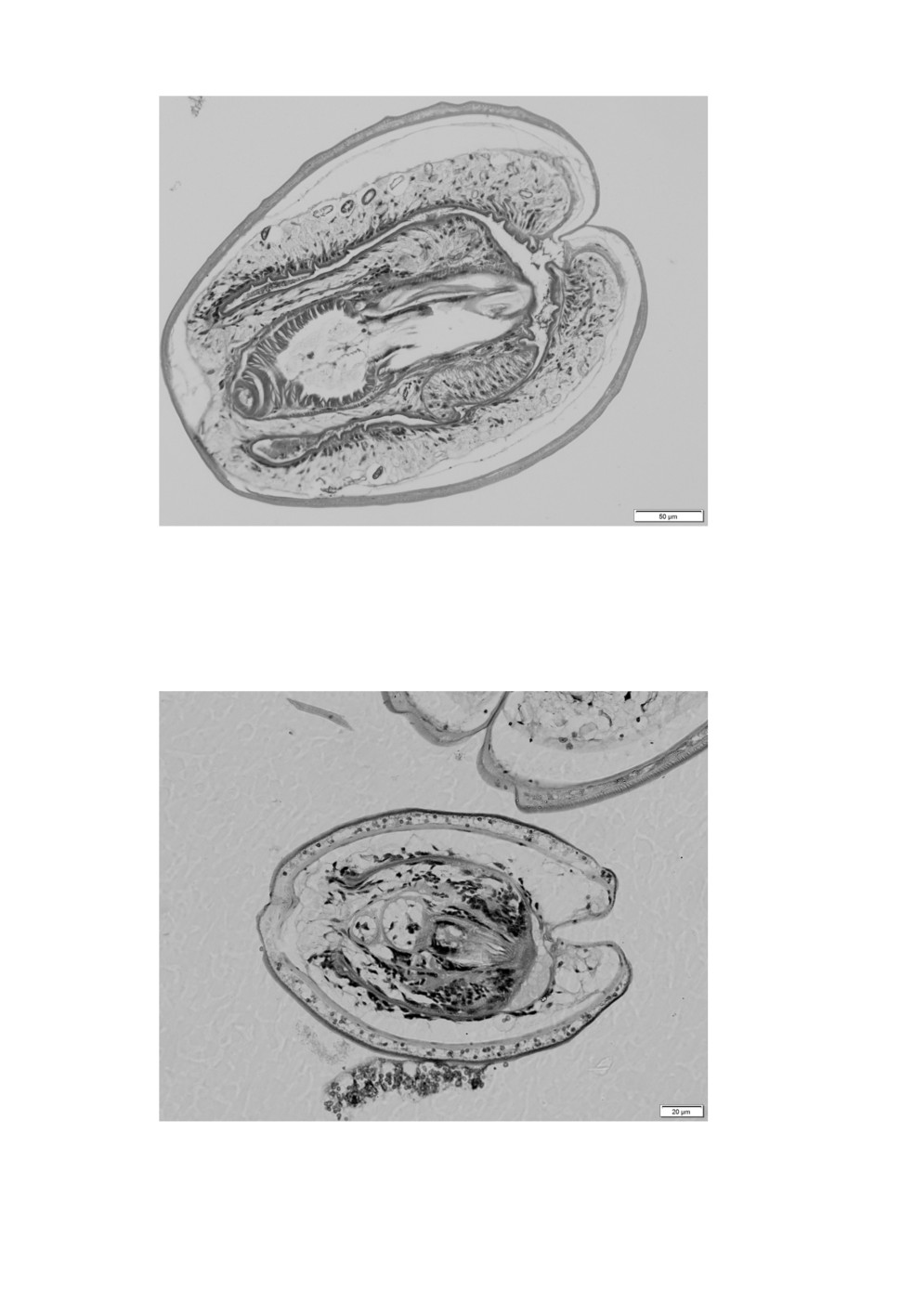

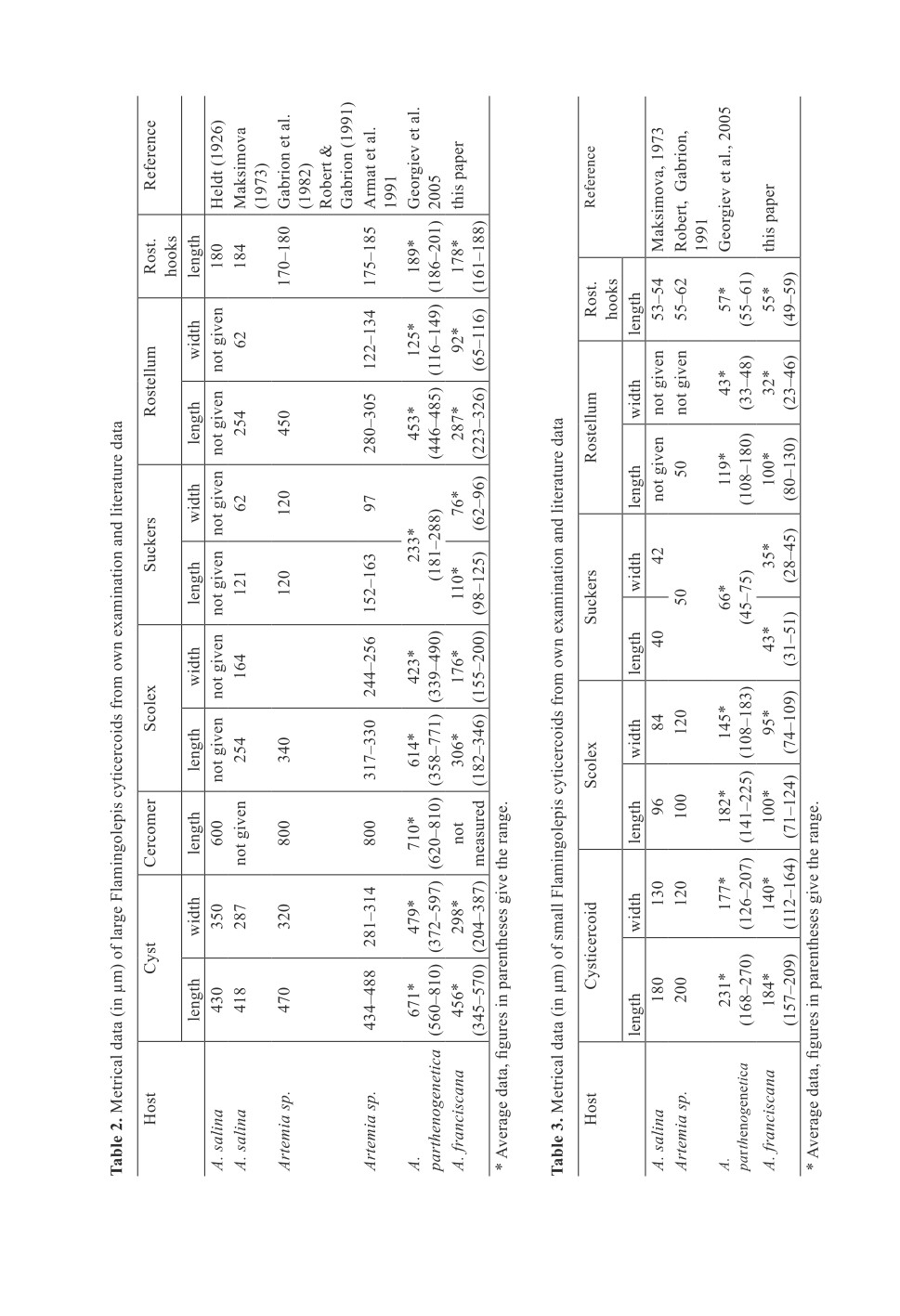

Tab. 2 and 3 and compared to literature data. Histological examination showed that the wall

of both cysticercoids consists of three layers (Figs 5, 6). Outer and inner layers are thin and

compact while the intermediate stratum is wider and seem to be more fluffily. PAS staining

revealed that the highest concentration of calcareous bodies is in tissues of the neck region,

surrounding the scolex (Fig. 7).

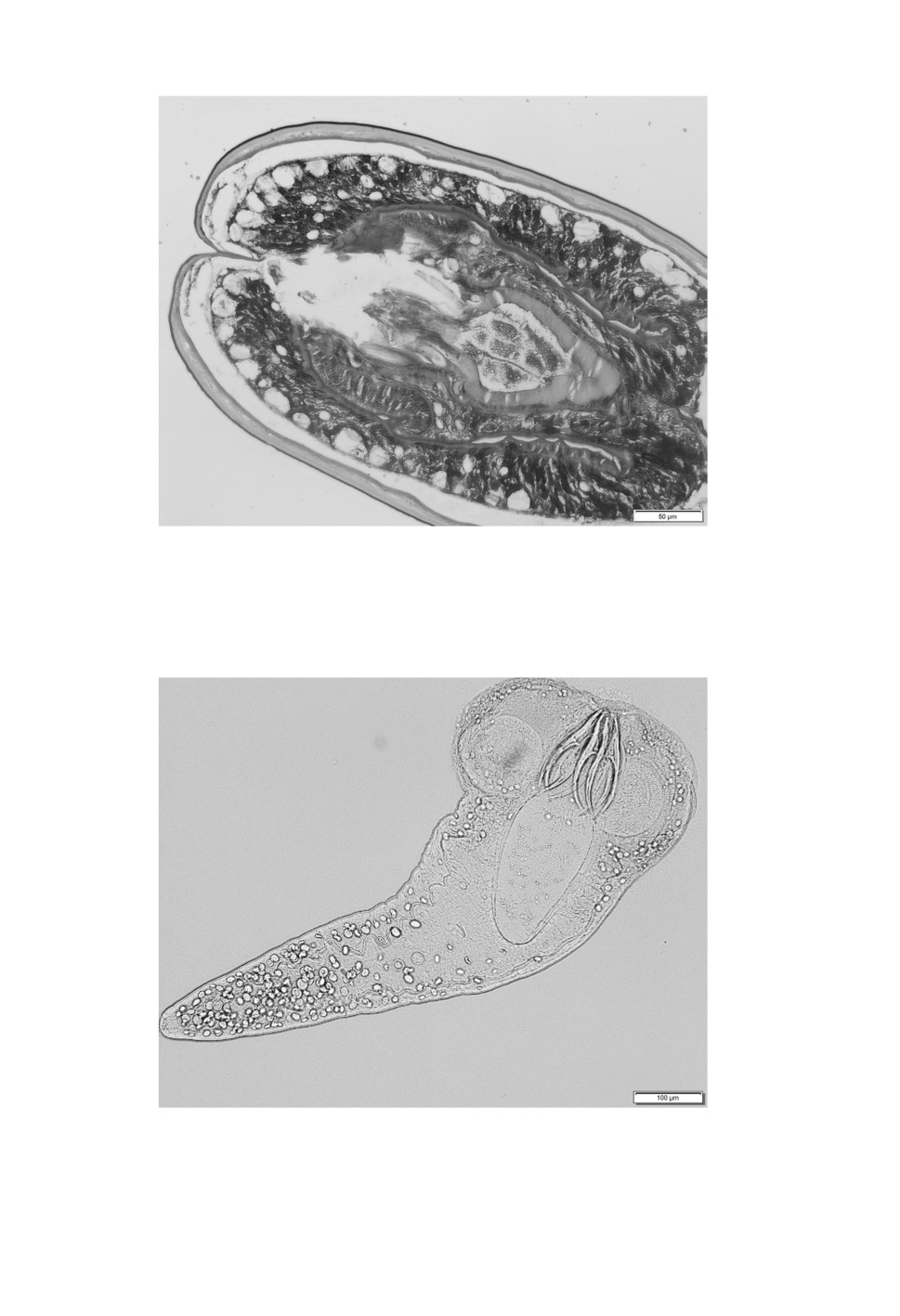

Five large and one small cysticercoid hatched in PBS (Figs 8, 9). Amongst the examined

material there were two cysts measuring 214-239 x 172-177 µm that were slightly bigger

than any other of the small cysticercoids. The most striking difference were rostellar hooks

of 82 and 84 µm in lengths with blades of 43 and 48 µm (Fig. 10).

Despite the relatively high number of Eurycestus cysticercoids seen in glycerin cleared

shrimps no cysticercoids of this genus were detected after treatment with artificial gastric

juice.

Table 1. Prevalence and burden and their 95% confidence intervals (C.I.) of cysticercoid infection in

300 Artemia fanciscana collected from Godolphin lakes in Dubai in May 2018

Number

Prevalence

Burden

Cysticercoid

Host sex

of

type

(%)

95% C.I.

average

95% C.I.

range

infected

Flamingolepis

(large)

132

98.5

94.7;99.8

5.52

5.08;5.99

1-12

males

Flamingolepis

(n=134)

(small)

52

38.8

30.5;47.6

1.81

1.54;2.12

1-5

Eurycestus

spp.

83

61.9

53.2;70.2

1.14

1.06;1.29

1-4

females

Flamingolepis

(n=166)

(large)

165

99.4

96.7;100

7.64

7.08;8.3

1-24

Flamingolepis

(small)

72

43.4

35.7;51.3

2

1.72;2.39

1-7

Eurycestus

spp.

104

62.7

54.8;70.0

1.15

1.08;1.23

1-3

445

Figure 1. Large Flamingolepis cysticercoid in the distal thorax of A. franciscana with

a relatively short cercomer, not longer than the double of the cyst length

Figure 2. Small Flamingolepis cysticercoid with a coiled long, thin cercomer

in the abdomen of A. franciscana

446

Figure 3. Large Flamingolepis cysticercoid after treatment of infected brine shrimps

with artificial gastric juice.

Figure 4. Small Flamingolepis cysticercoids after treatment of infected brine shrimps

with artificial gastric juice.

447

Figure 5. Histological section of a large Flamingolepis cysticercoid.

The thin wall consists of three layers.

Figure 6. Histological section of a small Flamingolepis cysticercoid.

Compared to the total size of the cysticercoid, its wall is relatively wide

448

Figure 7. PAS stain of a histological section of a large Flamingolepis cysticercoid show

a dense concentration of calcareous bodies in the tissues surrounding the scolex.

Figure 8. Hatched scolex of a large Flamingolepis cysticercoid with a retracted rostellum

after peptic digestion of the host and neutralization in PBS. Contrary to invaginated cysticercoids

the suckers are round. The basal part of the rostellum reach deep into the neck region.

450

Figure 9. Hatching scolex of a small Flamingolepis cysticercoid with an everted rostellum

after peptic digestion of the host and neutralization in PBS.

Figure 10. Flamingolepis cysticercoid

with 84 µm long rostellar hooks.

451

Discussion

Brine shrimps of the genus Artemia act as intermediate host for a number of cestode

species and cysticercoids of at least 16 different species were described in the literature.

In publications on cestode larval stages in Artemia spp. from hypersaline inland waters

in Asia (Kazakhstan and United Arab Emirates) and salters of the Mediterranean costs of

southern Europe and northern Africa Flamingolepis cysticercoids with eight skrjabinoid

rostellar hooks were reported. The prevalence and burdens of these cysticercoids in the current

sample were extraordinary high. In a previous publication on A. franciscana in the Godolphin

lakes (Sivakumar et al., 2018) it was shown that there were considerable variations in the

cysticercoid prevalence throughout the annual cycle. When water temperatures in June exceed

35 oC brine shrimps die, leaving resistant metabolic inactive cysts behind. In connection

with the refilling of the ponds and falling temperatures in autumn, cysts hatch and the

artemias gain life again attracting large amounts of waders and shore birds that contaminate

the habitat with cestode eggs. This resulted in a relatively high prevalence of 16 % already

in November. Falling temperatures in winter reduced the activity and food intake of the

crustaceans and led to lower prevalence rates in the following months. Rising temperatures

in spring resulted again in increasing activity of the brine shrimps and subsequently increased

cysticercoid prevalence. The highest prevalence rate of 70 % in that research was found in

May. Out of a total of 1.840 A. franciscana examined over an 8 month’s period, large and

small Flamingolepis cysticercoids were present in 25.3 and 10.7 % respectively.

Spasskij and Spasskaja (1954) erected the genus Flamingolepis and used F. liguloides as

type species. F. liguloides was mentioned for the first time as Halysis liguloides by Gervais

(1847). The original description supported by a drawing describes the cestode as small (60

mm) and slender (2 mm), with a globose scolex bearing four suckers and a small rhynchus2.

Lühe (1898) who examined intestinal parasites of greater flamingos in Tunisia recognized

the same cestode species by the specific appearance of its strobili resembling the body

of a ligula and added other essential morphological details like the unilateral situation of

genital pores and diameter of suckers. The most important completion however, was the

presence of eight slim and elongated rostellar hooks measuring 130 µm in length with blade

and handle being 70 and 60 µm long, respectively. The maximum width of the hooks was

30 µm at the guard. Lühe (1898) described a further cestode, Flamingolepis megalorchis

(Lühe, 1898), that consisted only of 30 to 40 segments and stroke because of three large

testes. Rostellar hooks had the same shape as F. liguloides but measured only 90 µm. He

also put Flamingolepis caroli (Parona, 1886) as junior synonym for F. liguloides. Cohn

(1901) reexamined F. liguloides collected by Lühe (1898) and enhanced the description by

a histological study of hermaphrodite segments. With a maximum length of 40 mm Lühe’s

cestodes were 2 cm shorter than described by Gervais (1847) and histological sections did

not reveal any traces of a uterus, indicating their prepatent status. Based on these histological

2 Gervais (1847) description did not mention rostellar hooks. They most probably got lost during preparation. The

main feature of the cestode was the ligula like strobila.

452

sections, Fuhrmann (1906) described the configuration of the testes which are arranged

in the shape of a triangle (type III). Linstow (1906) published a description of helminths

of the Colombo museum. Amongst them was a 75 mm long cestode from flamingo with

short but relatively broad segments. The scolex carried eight slim 140 µm long hooks. It is

worth mentioning that Shachtatinskaja (1952) mentioned a Hymenolepis species found in the

flamingo in Azerbaidjan. The description and the pictured scolex3 matched with F. liguloides.

In the collection of the Naturkundemuseum of Berlin there is a syntype (5226-E) of

Flamingolepis flamingo (Skrjabin, 1914) from greater flamingo of unknown origin. According

to Skrjabin (1914), the cestode was 18-25 mm long and up to 1 mm wide. The long rostellum

(150 x 37 µm) was armed with eight hooks, 62 µm in length.

Scientists from Kazakhstan published the description of two further flamingo cestodes from

Tengiz lake in Kazakhstan. Flamingolepis dolgushini Gvozdev and Maksimova, 1968 with

a length of up to 10 mm and a maximum width of 0.96 mm had relatively large suckers of

170 µm in diameter and a rostellum armed with eight skrjabinoid hooks of 176-182 µm in

length. Their blades measured 103 µm. The basal part of the rostellum reached deep into

the neck region. The other species, Flamingolepis tengizi Gvozdev and Maksimova, 1968,

measured only 5-6 mm with a maximum width of 1.2 mm. The rostellum was armed with

eight skrjabinoid hooks in a length of 53 µm, length of the blade was 28 µm.

The most reliable features to allocate a cysticercoid to the adult cestode are number, shape

and length of rostellar hooks. In this regard, it is difficult to understand why large cysticercoids

were determined as F. liguloides by Gabrion et al. (1982).

The description of cysticercoids in this paper is based on a large number of examined

cysticercoids. Georgiev et al. (2005) measured each 14 Flamingolepis cysticercoids of species

they believed to belong to F. liguloides and F. flamingo, respectively. Other researchers gave

only measurements not mentioning the number of examined specimens (Tabl. 2 and 3).

Measurements of the large cysticercoids in the own material matched with data published

by Heldt (1926), Maksimova (1973), Gabrion et al. (1982), Robert, Gabrion (1991) and

Amat et al. (1991) while parameter established by Georgiev et al. (2005) exceeded those

measurements. Measurements of the small cysticercoids coincide with those given by

Maksimova (1973) for those of F. tengizi and by Robert and Gabrion (1991) and Georgiev

et al. (2005) for those of F. flamingo.

Based on the size of rostellar hooks it can be excluded that large cysticercoids belong to

F. liguloides and it is more likely that they are F. dolgushini while small cysticercoids are

the larval stage of F. flamingo and F. tengizi has to be treated as its junior synonym. The

two other Flamingolepis cysticercoids had rostellar hooks comparable to F. megalorchis.

3 The scolex is pictured in a book by Spasskaja (1966).

453

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Mr. Vishvanatan from pathology department of the Central

Veterinary Research Laboratory for producing stained histological sections of cysticercoids.

Special thanks go to Prof. Dr. D. Erhan (Institute of Zoology Chisinau/ Republik of Moldova)

to Prof. Dr. V. Kharchenko (Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, Kiev/ Ukraine) and to Prof.

Dr. S. Rehbein (Boehringer-Ingelheim, Rohrdorf/ Germany) for their help in acquisition of

historical literature sources.

References

Amat F., Illescas M.P., Fernandez J. 1991. Brine shrimps Artemia parasitized by Flamingolepis liguloides (Cestods,

Hymenolepididae) cysticercoids in Spanish Mediterranean salters. Vie et Milieu 41: 237-244.

Asem A., Rastegar-Pouyani N., De Los Ríos-Escalante P. 2010. The genus Artemia Leach, 1819 (Crustacea:

Branchiopoda). I. True and false taxonomical descriptions. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research

38 (3): 501-506.

Cohn L. 1902. Zur Anatomie und Systematik der Vogelcestoden. Abhandlungen der Kaiserlichen Leopoldinisch-

Carolinischen Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher, 79: 271-450.

Fuhrmann O. 1906. Die Hymenolepis-Arten der Vögel II. Centralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde 42:

620-628, 730-755.

Gabrion C., Mac Donald G. 1980. Artemia sp. (Crustacé, Anostracé), hotê intermédiaire d’ Eurycestus avoceti

Clark, 1957 (Cestode Cyclophyllide) parasite de l’avocette en Camargue. Annales de Parasitologie Humaine

et Comparée 55: 327-331.

Gabrion C, MacDonald-Crivelli G., Boy V. 1982. Dynamique des populations larvaires du cestode Flamingolepis

liguloides dans une population d’ Artemia en Camargue. Acta Oecologica 3: 273-293.

Georgiev B.B., Sanchez M.I., Green A.J., Nikolov P.N., Vasilieva G.P., Mavrodieva R.S. 2005. Cestodes from

Artemia parthenogenetica (Crustacea, Branchipoda) in the Odiel Marshes, Spain: a systematic survey of

cysticercoids. Acta Parasitologica 50: 105-117.

Gervais M.P. 1847. Sur quelque Entozoaires Taenioides et Hydatides. Académie des Sciences et Letters de

Montpellier. Mémoires de la Section des Sciences 85-103.

Gvozdev E.V., Maksimova A.P. 1979. Morphology and life cycle of Gynandrotaenia stammeri (Cestoidea:

Cyclophyllidea) parasite of the flamingo. Parazitologiya 13 (1): 56-60. [in Russian]

Heldt H. 1926. Sur la presence d’une cysticercoide chez Artemia salina L. Station Oceonographique de Salammbo

(5): 1-8.

Linstow O. von 1906. Helminthes from the collection of the Colombo Museum. Spoila Zeylanica 3: 163-188.

Lühe M. 1898. Beiträge zur Helminthenfauna der Berberei. Sitzungsberichte der königlich preussischen Akademie

der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (2): 619-628.

Maksimova A.P. 1973. Branchiopods - intermediate hosts of cestodes of the family Hymenolepididae. Parazitologiya

7 (4): 349-351. [In Russian]

Maksimova A.P. 1977. Branchiopods - intermediate hosts of the cestode Anomolepis averini (Spassky et Yurpalova,

1967) (Cestoda: Dilepididae). Parazitologiya 11 (1): 77-79. [In Russian]

Maksimova A.P. 1981. Morphology and life cycle of the cestode Confluaria podicipina (Cestoda: Hymenolepididae).

Parazitologiya, 15 (4): 325-331. [In Russian]

Maksimova A.P. 1986. On the morphology and biology of the cestode Wardium stellorae (Cestoda, Hymenolepididae.

Parazitologiya 20 (6): 487-491. [In Russian]

Maksimova A.P. 1987. On the morphology and life cycle of the cestode Wardium fusa (Cestoda, Hymenolepididae.

Parazitologiya 21 (2): 157-159. [In Russian]

Maksimova A.P. 1988. A new cestode, Wardium gvozdevi sp. n. (Cestoda: Hymenolepididae), and its biology. Folia

Parasitologica 35: 217-222.

Maksimova A.P. 1991. On the ecology and biology of Eurycestus avoceti (Cestoda: Dilepididae). Parazitologiya

25 (1): 73-76 [In Russian]

454

Mura G. 1995. Cestode parasitism (Flamingolepis liguloides Gervais, 1847 Spassky &Spasskaja 1954) in an Artemia

population from south-western Sardinia. International Journal of Salt Lake Research 3: 191-200.

Robert F., Gabrion C. 1991. Cestodoses de l’ avifaune Camarguaise. Rôle d’ Artemia (Crustacea, Anostraca) et

stratégies de recontre hôte-parasite. Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et Comparée 66: 226-235.

Rozsa L., Reiczigel J., Majoros G. 2000. Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. Journal of Parasitology 86:

228-232.

Schuster R.K. 2019. On two morphologically different cysticercoids of the genus Eurycestus (Cestoda: Dilepididae)

in Artemia franciscana (Arthropoda: Artemiidae) in a hypersaline pond in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Helminthologia 56: 151-156.

Shachtatinskaja Z.M. 1952. Helminthfauna of domestic and wild water birds of Azerbaidzan SSR. Thesis 572 pp.

[in Russian]

Sivakumar S., Hyland K., Schuster R.K. 2018. Tapeworm larvae in Artemia franciscana (Crustacea: Anacostraca) in

the Goldolphin lakes of Dubai (United Arab Emirates) throughout an annual cycle. Journal of Helminthology

Skrjabin K.I. 1914. Beitrag zur Kenntnis einiger Vogelcestoden. Centralblatt für Bacteriologie und

Infektionskrankheiten. Originale Abteilung 2 (75): 59-83.

Spasskaja L.P. 1966. Cesodes of birds of the USSR. Hymenolepididae (in Russian). Moskva, Nauka, 698 pp. [in

Russian]

Spasskij A.A., Spasskaja L.P. 1954. Construction of the system of hymenolepididae, parasites of birds Trudy

GELAN 7: 55-119. [in Russian]

О ЦИСТИЦЕРКОИДАХ РОДА FLAMINGOLEPIS SPASSKIJ & SPASSKAJA, 1954

(CESTODA: HYMENOLEPIDIDAE),

ПАРАЗИТИРУЮЩИХ В ARTEMIA FRANCISCANA KELLOG, 1906

(ARTHROPODA: ARTEMIIDAE)

В ДУБАЕ, ОБЪЕДИНЕННЫЕ АРАБСКИЕ ЭМИРАТЫ

© 2019 R.K. Schuster

Ключевые слова: Artemia franciscana, Cestoda, Flamingolepis, цистицеркоиды, Дубай.

РЕЗЮМЕ

Исследование 300 особей Artemia franciscana Kellog, 1906 в Дубае выявило их необычайно

высокую зараженность цистицеркоидами - 99 %. При этом, среди личинок цестод преоблада-

ли крупные и мелкие цистицеркоиды рода Flamingolepis. После переваривания ракообразных

в искусственном желудочном соке было изолировано множество цистицеркоидов, из которых

120 крупных и 60 мелких цист были изучены в световом микроскопе. Часть материала была ис-

пользована для гистологического исследования. В результате крупные цисты эллиптической фор-

мы размером 345-545 х 204-387 мкм с ростеллярными крючками 161-188 и лезвием 91-115 мкм

были определены как F. dolgushini, а цисты размером 157-209 х 112-164 мкм с ростеллярными

крючками 49-59 мкм и лезвием 25-33 мкм были приписаны F. flamingo. Материал содержал еще

один вид, предположительно F. megalorchis, с ростеллярными крючками размером 82-84 мкм.

455